5th - 20th September 2012

Vietnam

9201

- 9900km

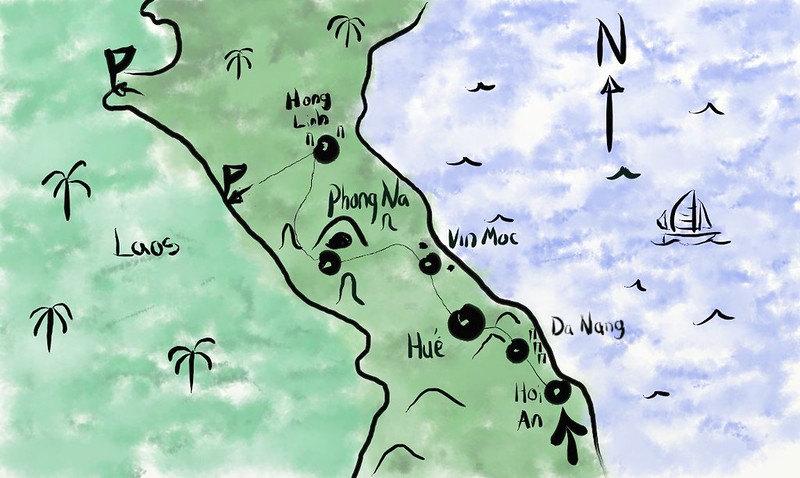

Da

Nang – Huế – Ho Xa – Phong Nha – Hong Linh

Those of you who have been following our adventures over the past year will have noticed a distinct lack of activity here lately. Don't worry, we are safe and well,

it's just that China's Great Firewall got between us and the blog, and by the time we figured out how to get round it time had gotten so tight we barely had time to eat, let alone type.

No excuses now

though, we’re back home in frosty old England with time to kill. But already

these stories have begun to mist over as real life rumbles back into existence.

Memories of riding bikes through jungles and mountains seem unreal, more than a

world away. So let's dig them up, dust them off, and relive some of

the action. Come computer! Whisk me out of this cold Tuesday morning and back

to... oh shit, it's Vietnam still isn't it.

Rough ride

We still don’t fully understand why Vietnam

was so hard on us. Bad luck? Plenty of other travellers love the place, and besides, adventure isn't meant to go easy on you, it's supposed to be tough and teach you a thing or two about adversity. But I find it hard to draw anything positive from our encounters in Vietnam. I want to be clear that the majority of people

we met were perfectly civil. The problem lay with this sizeable minority of

absolute bastards who took every opportunity to rip us off, intimidate us, and

treat us like dirt. When this happens so frequently you can never relax, you're always on guard, and

eventually the odds catch up with you and something really unpleasant happens.

At the very beginning of this trip we said that we'd keep going until it

stopped being fun. Well, in Vietnam, it definitely stopped being fun.

It’s strange falling out with a country like this. And a

real shame. On the morning of the 5th of September Liv and I stood

on the front steps of the Ancient House Resort, waving as a taxi pulled away

with Liv’s parents. One of the best weeks of the trip was over. After enjoying

the company of Chris and Graham it was not easy getting motivated about cycling

again. We dawdled by the pool for most of the morning, before finally wheeling

our bikes down the path and back on to the horn honking mayhem of the

road.

We weren't exactly Bradley Wiggins when we got

going. The next few days were a staccato affair of half days and days off as we

crept northwards along the highway. Not far up the coast lay the beach resort

city of Da Nang. Lax planning laws had turned the beachfront into a

post-apocalyptic clamour of half-built hotels and concrete, but we needed a

day off here to get spare parts and supplies. We scored a cheap room deep in

the city, and the next morning found a bike shop without much hassle. The local

supermarket was well stocked too, full of fruit and biscuits and other goodies

that cyclists crave. Their security didn't think much of us though, so we spent

most of the time being followed by two openly suspicious guards. To be fair we

did look a bit trampy, but there are more subtle ways of monitoring potential

thieves than literally leaning over their shoulder to stare at whatever they’re

handling.

Shopping and servicing bikes didn’t amount to much of a

day off, but we were off again the next morning. Coming out of Da Nang we hit

the large hill made famous by the Top Gear team - rather originally known as

‘Top Gear Hill’. Glad we cycled it. There’s nothing quite like reaching the top

after a hot sweaty climb and burning down the other side for half an hour with

the wind in your face. You don’t get that when an engine’s done the work for

you. Not the same.

The road flattened out, wet paddies spread across the

landscape, and the sun splashed down into a ripe evening of reds and oranges.

By the time we reached the city of Huế it was well past dark, but luck was on

our side and led us to a great little place called the ‘Why Not?’ guesthouse. A

lovely young woman welcomed us inside and offered us a good deal if we stayed a

few nights. A couple more days off? Why not. I bet they get hundreds of people

like that.

For one hundred and fifty years Huế was the imperial capital of Vietnam, but then communism came along and made monarchic power unfashionable. Although the American War blew chunks out of some areas, tantalising reminders of Vietnam’s courtly past still remain, and they are well worth a nosey.

After a few

restful days among the pizza parlours of the tourist district, Liv and I

ventured across the river, under the old city gateway and into the imperial

compound. During the reign of the emperors anybody caught trespassing here was

liable to be executed, giving rise to its other name ‘The Forbidden City’.

Thankfully the authorities are a bit more welcoming these days, and we just had

to fork out a few dollars for a ticket.

As we passed

through the colossal gateway and emerged into the compound we were greeted by

carved dragon totems that flanked the walkway. A hall of gilded pillars lay

ahead of us, stretching wide and low, a building in cinematic widescreen, and

the setting for past exchanges between the country's wealthy elite, and the

mighty emperor himself.

Beyond this

palatial boardroom the compound yawned open into a vast courtyard many hundreds

of meters

Beyond this

palatial boardroom the compound yawned open into a vast courtyard many hundreds

of meters across, ringed by walled enclosures that sported their own wood-beamed halls and elegant gardens.

No doubt this

was only a whisper of its former magnificence, but it was enough to get our

imagination going. As we roamed the compound, images flickered through our

minds of ladies strolling the gardens, the furious emperor banishing greedy

merchants, and black clad assassins padding silently over moonlit roofs.

Huế was a fine

place to get stuck in for a few days, thanks largely to the warmth and kindness

we received from the young lady working at our guesthouse. If I seem to be

making a big deal out of this it’s because having somewhere friendly to escape

to was becoming increasingly important. We didn't seem to be meeting many

friendly people out here. Much of the time the default attitude towards us was

of contempt. Street vendors exchanged sly comments and laughed at us before

handing us our food, shop keepers shoved us out the way as we browsed their

aisles, bills would sky rocket unless we checked the price first, and time

after time our smiles and hellos were met with blank stares and silence. There

was a background hiss of something unpleasant that was hard to put a finger on.

Being over charged is fine, it comes with the territory, but there was

something malicious about this, something we'd never experienced before.

The day’s ride

out of Huế was long. We spent the morning winding through shivering rice plains

as the wind dragged clouds off the hills. Rain hung like fog to the west for a

time, steadily sweeping in until it came clattering down on us by mid morning.

We sat out the weather with a coffee, then pushed on out of the lanes to join Highway

1. This is the main road that runs the entire length of the country so we were

expecting some serious traffic. Thankfully, we were wrong. Just one lane going

each way, and only a scattering of vehicles along it. No excuse to drop our

guard though, because the roads out here aren’t governed by anything even

remotely resembling a highway code.

It’s not an

exaggeration to say that Vietnamese driving is the worst we've ever

encountered. Consistently so. Acts of reckless stupidity crash right

into you with a frightening regularity. There’s no logic to it. I struggle to

grasp how anybody could make the decisions that we saw careering past us so

often in Vietnam. One incident that really captures the attitude took place

that afternoon as we were pedalling along the highway. There were a few cars

and scooters around us but, as I've said, it wasn't particularly busy. We were

just pedalling along, minding our own business, as a trickle of motor vehicles

passed us by.

Then a bus swung out of the oncoming traffic and came hurtling straight towards us, sending a cold feeling down my fingers. It was an ill-timed move to overtake somebody which put this homicidal bus on a collision course with the entire northbound lane of traffic. The bus driver had seconds to get back over before he smashed into the scooter in front of me, and he wasn't going to make it. The scooter calmly began to pull over like nothing was wrong, and then I realised. This bus driver knew that he was the biggest thing on the road. He's figured that everyone will get out of his way if he drives straight at them, because nobody fancies their chances in a head on collision with a bus. So the entire right side of the highway, a dozen vehicles, were forced to bail off the road and onto the grass. A second later this behemoth twat came thundering past like a locomotive, horn blaring.

Then a bus swung out of the oncoming traffic and came hurtling straight towards us, sending a cold feeling down my fingers. It was an ill-timed move to overtake somebody which put this homicidal bus on a collision course with the entire northbound lane of traffic. The bus driver had seconds to get back over before he smashed into the scooter in front of me, and he wasn't going to make it. The scooter calmly began to pull over like nothing was wrong, and then I realised. This bus driver knew that he was the biggest thing on the road. He's figured that everyone will get out of his way if he drives straight at them, because nobody fancies their chances in a head on collision with a bus. So the entire right side of the highway, a dozen vehicles, were forced to bail off the road and onto the grass. A second later this behemoth twat came thundering past like a locomotive, horn blaring.

I suppose in

theory this system of ‘survival of the biggest’ might just work, but it

requires drivers with some degree of common sense, and

as we have learnt, you really can’t rely on that out here.

I suppose in

theory this system of ‘survival of the biggest’ might just work, but it

requires drivers with some degree of common sense, and

as we have learnt, you really can’t rely on that out here.

I had two people

crash into me in Vietnam. The first happened on the way out of Da Nang. A man

on his scooter wanted to exit a roundabout and wasn’t concerned that there were

six lanes of tightly packed traffic in his way. He didn't make it very far and

wound up thumping into the first thing he came across, which was my front

wheel. I just about managed to stay upright but it nearly caused a pile up

behind me, though perhaps that was his intention after all. The accident

created a gap in the flow of traffic and this guy seized his chance. He hauled

his scooter away from me, pointed it at his now-clear exit, and he accelerated

away across the road. I watched with amazement as he departed, before I was

harried back into action as the traffic came banging and beeping past me again.

And that wasn’t

even the worst. That proud honour goes to a woman I met, rather abruptly, a

couple of weeks previous to this when we were cycling through the countryside

on our way to Hoi An. We were making our way up a hill one afternoon, crawling

along in lowest gear. The road was completely straight and empty, there were no

junctions, and except for a few houses set back there was nowhere any hazard

could emerge from. We just had to concentrate on getting up this hill.

I heard the

whine of a motor scooter and glanced across to see a woman revving towards me

from her driveway. Liv was a little way ahead, which meant that as far as this

woman was concerned I was the only animate object on an otherwise empty road.

The thought of a collision didn't even cross my mind because that would require

a catastrophic breakdown of basic survival instincts, and evolution would have

ironed those things out billenia ago.

She did seem to

be in a rush. Her engine went up an octave, but that was fine, she had about

fifteen feet of space either side of me to get round. Her driveway was long

too, and afforded her ample opportunity to manoeuvre. For there to be an

accident here, I might have surmised if I’d thought it necessary, she would

have to accelerate unflinchingly and not make any attempt to turn. There will

not be a crash here, I didn't think, because nobody's that stupid.

You know what

happens next. The whine of the engine terminated abruptly as the scooter thumped into my side. There was a stunned pause in which I tried to catch her eye to

beg an explanation (what’s the international facial expression for “Are you

insane?”). But as with the roundabout collider, she didn't even bother to look

at me. Without so much as a glance she pushed past, farted out a cloud of

exhaust, and buzzed off up the hill. There's something uncanny about the

attitude on the roads out here, like a thousand despondent teenagers, heads

down, riding the bumper cars.

Down turn

So it was a long

day riding out of Huế. As the evening set in smoke trailed across the fields from

burning heaps of vegetation, and it was night by the time we rolled in to a little

junction town and began fishing for a room. We found one soon enough,

and by scribbling some figures down in my notepad I asked the girl at reception

if she had any rooms going for 150'000 dong. She did. After inspecting the room

and triple checking the price we filled in the

forms, handed over our passports, and hauled our bags up the stairs. As we

dumped the last of them on the bed there was a knock at the door. The

receptionist had some news for us, the price had just doubled.

So, here we were

again, not entirely surprised but very tired, and very pissed off. I pointed to

the figures I’d shown her in my notepad and reminded her that she had agreed to

this on several occasions. She shook her head, then tried to barter with us,

“180'000.”

I'd thought it

had been a bit too easy, ask for a room at a reasonable rate and get told you

can have it at that price right away. The girl had evidently failed to

overcharge us, so the owner had ordered her upstairs to force renegotiations.

I stormed

downstairs to have it out with the manager, a black haired lady of short

stature and shorter scruples. She knew exactly what was going on. Without

looking at me she calmly wrote 200'000 on a scrap of paper and pushed it over

the counter. Now, this was not a crazy amount of money, and we probably would have

taken that in the first place, but it wasn't the price we’d agreed.

Didn’t she realise we’re British? We're incapable of letting these things

slide.

Of course they

had our passports now so we couldn't just do a runner the next morning. Our

choice was to either get screwed over, or head off into the night to find

somewhere else. It was late. It was dark. Who knew what the next hotel would be

like. Who knew if there even was one. What an abysmal end to the day.

I didn’t have

many cards to play, so I decided to bluff it and told her we couldn't possibly

stand for this and were going to leave at once. I jogged back upstairs to

discuss tactics with Liv, but as we were talking there was a knock at the door.

It was the girl from reception.

“OK.”

I got my trusty

notepad out and pointed at the figures. “150'000 dong?”

She nodded.

I bolted

downstairs to confirm all of this with the manager. I wanted to be sure we were

on the same page, preferably the one in my notepad that had 150'000 dong

written on it.

“150'000 then?”

I asked the manager, and then a funny thing happened.

She nodded

reluctantly and then whipped her palm up in front of my face. She turned her

nose up and began flicking her head from left to right like an affronted horse.

After a few of these theatrical shows she spun round and marched out.

I was now the

only person in the lobby, and I sighed. I was convinced she knew she had been

caught out, but she put on this little show anyway. It was funny, and a little

bit sad. It stank like a fraudster trying to save face, which it probably was.

But no matter, our ordeal was over.

I ascended the

stairs for the umpteenth time that evening, more than an hour after we'd first

walked in. I was worn out, tense, but relieved. Liv was standing in the corridor,

her expression told me something was wrong.

“Guess what?”

she said. “We can't lock our door. It's broken.”

Underground retreat

We had crossed into the demilitarised zone the previous day

and that meant, rather counterintuitively, there were lots of old military sites nearby. Just getting a room felt like enough of a battle, but we were keen to learn about the Vietnamese side of the war. So

against our better judgement we took a day off in our unpleasant little

rip off hotel, and set out to explore the area.

A few kilometres east lay the Vinh Moc Tunnels, an

underground network of passageways dug into the hills to shelter and sustain an

entire community during the conflict. Not just soldiers, but whole families lived

underground here to escape the bombers. Sleeping, eating, bathing, even raising

animals in a constricted maze of compacted earth.

Thinking back to our hotel manager I thought it would be

no bad thing if she was thrust into some kind of awful war. Hate breeds hate,

it's true. But as we cycled along the lanes that morning we were joined by two

young lads on their bikes who would brighten our moods. They spoke no English,

but we could tell by their inquisitive looks and friendly smiles they weren't

up to any mischief. So we rode together, and once we'd locked our bikes up at

the entrance they came with us as we descended into the tunnels.

Thinking back to our hotel manager I thought it would be

no bad thing if she was thrust into some kind of awful war. Hate breeds hate,

it's true. But as we cycled along the lanes that morning we were joined by two

young lads on their bikes who would brighten our moods. They spoke no English,

but we could tell by their inquisitive looks and friendly smiles they weren't

up to any mischief. So we rode together, and once we'd locked our bikes up at

the entrance they came with us as we descended into the tunnels.

We had the place to ourselves and it was a great afternoon.

The four of us wandered down the dimly lit passageways, and crept down

forbidden routes into pitch darkness. Sometimes we’d emerge by the

sea, other times in damp chambers, occasionally a dead end - ample

opportunities for startling each other with a well timed “Boo!” The tunnels

descended to lower vaults where life-size dummies were arranged in alcoves,

ostensibly to teach us about life in the tunnels, but really only succeeding in terrifying us whenever we ran into them.

On the way out we bought a round of pop for the kids, and

then rode back along the lanes together. We parted with smiles, a bit

frustrated that we couldn't say much else. The two lads pedalled off, and Liv

and I reluctantly headed back to our hotel.

So, the hotel. The night before we'd sorted a compromise.

Liv had gone downstairs to deal with the matter of the broken door, and we'd

been moved into a larger room with a working lock. They'd not talked about the

price with us, perhaps because they were as sick of it as we were, but we

decided since we were now in a bigger room we could offer to pay a bit more for

it anyway. That seemed to lift the cold atmosphere of the place somewhat – the

hotel manager began speaking to me again – and we figured that although we were

down on a few dong, we'd gained some vague notion about what it meant to save

face, although frankly I still felt about as welcome as a wet dog.

We departed early the next morning, and stayed on

the highway for an hour before breaking off onto the almost deserted Ho

Chi Minh highway. The scenery grew more beautiful and our legs more tired, as

the road rippled up through shallow hills.

By mid afternoon we descended into a expanse of cultivated

flatland surrounded by steep towers of limestone. This was the Phong Nha-Ke

Bang national park, a designated world heritage site famous for its caves and

beautiful scenery. Gazing at the landscape we couldn't help but think that the

authorities had seriously missed the point, having stamped UNESCO WORLD

HERITAGE SITE in ten foot letters right across the rocks. Idiots.

On our way into town we were greeted by a man on a

motorbike telling us to fuck off so we didn't have high hopes of getting along

here either. Mercifully our hotel turned out to be lovely. The trouble

was we didn't know that at the time. Everybody seems okay at first, and

then they make fun of you, hike the price, or steal your passports. Vietnam was

proving to be particularly draining. Despite our slow progress we decided

we needed another day off. We didn't kid ourselves, we didn't need an excuse

for it, but having some world class caves to explore nearby did make the

decision a little easier.

Despite having fruit thrown at us on the way there, and

some scooters try and drive us off the road on the way back, we considered our

day trip to the caves a success. After cycling a dozen kilometres or so we

locked the bikes up and clambered up the path to the entrance. Climbing down

through the mouth we found ourselves staring into an enormous underground

chamber. It was huge, big enough to accommodate a football stadium, and all

around lay these astonishing meringue-like formations composed over

thousands of years by dripping sediment. We descended the clanging metal staircase to the cave floor

and made our way along an old underground river bed surrounded by these

deranged natural sculptures.

It was dusk when we got back on the bikes, and although we had to contend with those nasty individuals swerving at us in the dark, the ride back was otherwise peaceful. Actually I nearly crashed right up a cows bum, and Liv's front light ran out of juice, but despite all of that the overriding memory I have is of tranquillity. Fireflies sparked in the hedges, cow bells jangled in the fields, and a pristine vault of stars was spread out above us. It was at least occasionally peaceful, and we needed a bit of that.

It was dusk when we got back on the bikes, and although we had to contend with those nasty individuals swerving at us in the dark, the ride back was otherwise peaceful. Actually I nearly crashed right up a cows bum, and Liv's front light ran out of juice, but despite all of that the overriding memory I have is of tranquillity. Fireflies sparked in the hedges, cow bells jangled in the fields, and a pristine vault of stars was spread out above us. It was at least occasionally peaceful, and we needed a bit of that.

Although there wasn’t much to do in the town, by now we

were getting on well with our hotel so we extended our stay and wallowed in the

hospitality. By the time we left we were in two minds about the road ahead. A

couple of restful days in a friendly hotel reminded us that getting a bed

didn't have to be a struggle. But we were in the north now, and although we had

heard conflicting accounts from travellers, a common theme was that the south

was friendly, the north much less so. With friends like these who needs

enemies, right? We set off up the road, fingers crossed, grimly prepared for

whatever was to come.

Trouble

There was no denying the landscape was beautiful. The empty

road led us along the base of a stunning grassy valley, up over lush hills, and

through serene rural villages. We surprised the owners of a rickety wooden shop when we showed up for lunch, but they were friendly, and smiled and nodded in approval as we wolfed down a bowl of their noodle soup. There were hardly any vehicles on the road all day, and everybody we met seemed

friendly for the first time in a quite a while. People smiled. Even the rowdy

alcoholic at our second noodle stop insisted we have some of his rice wine. And

then some more. And then we really had to be firm. But thank you. No. Thank

you.

At just the right time - as our muscles started feeling

sandy and the sunlight ran amber – we saw a sign for a guesthouse. It was a

basic room, but we were lucky to find anything at all this far out.

We ate a good dinner, sparked up some mosquito coils, and fell asleep.

|

| We found this thing fermenting in the restaurant that night. Does anybody have any idea what it is? |

The next morning started out equally perfect. The sky was pristine and the road was quiet. We stopped off at a shop by a railway track, and the owner came over and offered us some free bananas. We were the happiest we'd been since Hoi An, but all that was about to change.

We set off again, waving to the woman and smiling to

ourselves. The terrain looked set to go easy on us for the rest of the day, and there was a small

city within easy range.

“This is brilliant!” I shouted back to Liv, who beamed back

at me. We talked about this being the turning point, about how a final week

like this might make us forget about the hassle of the last few weeks.

In my excitement I got a bit ahead of Liv, and was pumping

along through a neat little village when I heard shouting behind me. I skidded

to a halt and turned to see Liv, a hundred metres behind me, getting off her

bike to confront two young men by the side of the road. Something had happened.

I sprang off my bike, spilling the contents of my handlebar

bag, and ran over to her.

“What the hell do you think you're doing?! What are you thinking? Hey? Look at me!”

The men wore dismissive sneers, and made brushing gestures

with their hands.

“Liv what happened?”

“These men just tried to grope me.” she turned back to the

two men, “You think you can just grab people like that? Hey!”

Things were happening fast. I stepped up to the men and

made my feelings known. They didn't understand a word we said but they got the

idea. But they never faltered in their aloofness, shooing us away and, as I

understood it, telling us we should stop making such a fuss.

A third man appeared from a doorway, a friend of theirs. As

he jogged over I began to feel very uneasy at the way things were going. There were

three of them now, and they were becoming increasingly aggressive.

One of the men suddenly ducked down and scooped up a rock

about the size of a lemon. The shouting tailed off and a horrible sensation sank through me. He wrenched his arm back and

hurled the rock, full force, straight at Liv. There was a thump and a gasp and

she was knocked staggering back.

Confused instinct drenched in fear sent me lurching towards

her attacker. But I stopped myself, or perhaps the fear did. Getting into a

fight with these three would end very badly. The man was picking up another

rock to throw, so I got between him and Liv. He threw a fierce glance at me. I

raised my hands up, backed off, and turned to Liv.

The rock had struck her hard on the hip and left a deep

bruise that was welling up with blood. She was in shock, and scared. I was

terrified. I turned around, suddenly fearing the men were about to pounce,

but in those few seconds they had vanished.

What the hell do you do? Villagers came and gathered around us, pointing at the discarded bicycles. We tried to explain

what had happened, but everybody seemed to think Liv had fallen off her bike.

We sat down for a minute to try and calm down, but people were staring and

asking lots of questions and we couldn't understand them. A woman who saw Liv's

wound came back with some oil to treat it, and another man tapped me on the

shoulder and pointed out that my ipod and wallet were scattered across the

road, easy pickings for thieves. These kind gestures went a long way on this the worst of days, but we were still shaking and afraid.

A police van appeared from somewhere and pulled over, it

was probably just a coincidence but now we had the chance to get those thugs arrested.

But we didn’t. Everything was getting hectic and I thought the best thing to do

was to get Liv out of there as soon as possible. To be quite frank I didn’t

hold high hopes of the police being much good to us anyway. I was done with

Vietnam.

Liv got to her feet and I picked her bike up off the road.

We pedalled away, shaking and in tears. Once we were out of sight from the

village we stopped by the side of the road and sat, there wasn't much to say.

As the shock faded our own guilt began to surface. Liv

chastised herself for losing her cool and shouting at the men, and I felt weak

and guilty at not having protected her. It took us weeks to settle our thoughts

and realise that sometimes you come up against people like that and there

aren’t always good ways of coming out of it. I think Liv is an incredible

person, for so many reasons, not least because she'll take on two men who try anything like that. And although my inaction probably stemmed from fear, it was fear

well grounded. I'm not a fighter, and even if I'd landed a good one on the guy

who threw the stone, things would not have stayed in my favour for long.

We were still in for a nasty couple of days though. The

suddenness of the attack was menacing, especially in such a small village, and

we were both incredibly nervous as we rode. Two motor scooters, on two separate

occasions that afternoon, made the effort of flicking us the finger and careful

enunciating a “Fuck you.” at us as they came past. They looked like they meant it too.

Then we got lost down the lanes, but despite speaking a

comprehensible level of Vietnamese many people just point blank refused to help

us when we asked for directions.

“Which way to Hong Linh?”

“No!” and they'd scowl at us, or turn their backs.

As we pedalled into town, washed out and emotionally

exhausted, children began jeering at us. “Hey! Give us money!” and their family

burst into laughter. We might have laughed too, but we had serious doubts about

Vietnam, the whole country felt gnarled. We pedalled off at speed, stomachs

fluttering.

We found a hotel just before dark, and the repellent

attitude just kept on coming. We were given a room with a ceiling that leaked

onto the bed, and when I went downstairs to request another room the two young

women behind reception just laughed.

“No rooms. Full.” they told me, grinning.

This was not true. The hotel was huge, ten stories at least

and there was nobody else around. “I need to move. Water. Dripping. Bed.”

They laughed together, and one imitated a drop with her

finger, plopping on her head. “Drip drip!” and they both laughed again.

I felt terrible about what had happened that day, and I was

damned if I was going to let these harpies ruin Liv's night as well. I was

going to stay here, badly pronouncing sentences from the phrasebook until they

got tired of their game. In the end I spent half an hour there, being laughed

at, then ignored. Eventually a middle aged man got up from one of

the sofas and walked over. He stepped behind reception and showed me a piece of

paper with some numbers on.

“Big. Small.” he pointed at two of the figures.

They were room prices, and revealed that on top of being

dumped in a leaking room we had been grossly overcharged. We were in a small

room, paying the same price as a big one. This guy was evidently the manager and

he had finally taken pity on me.

“Do you have rooms?”

“Yes.”

“And they cost this much?”

He shook his head and pointed at me. “English.” he said.

English people had to pay more.

“I've been in Vietnam for long enough mate. How about a

local price?”

I was tired and angry, I hadn't showered in a few days. I looked pretty desperate. He looked

me up and down, then finally nodded, and I was shown one of the dozens of empty

rooms.

Escape

Liv was determined she wasn't going to be driven out of the

country by what had happened. I wasn't so sure. We only had a handful of days

left on our visa and it was going to be a squeeze to make it to the border that we'd originally been shooting for. There was another way into Laos though, directly west of us, a day or two’s ride.

That morning as we wandered around the streets to try and

find an ATM the matter was settled. People shouted at us in the street, telling

us to get out of their city, and an old man made another grab at Liv then

cackled in our faces. It felt like we couldn't do anything back, in case the

whole city descended on us. It was decided, we were getting the hell out of

Vietnam.

There's no justification for behaviour like this,

but then again everything has its cause. Slightly north of Hong Linh lies Vinh,

an ancient city blown to pieces by successive fighting with the French and

Americans. This whole area was pulverized by the wars, and countless people

lost their mothers, fathers, sons and daughters. People seeking answers to the horrors here might easily leave with a nasty impression of the white westerners who did this. Hello, we're white westerners too.

We caught the bus to Vinh to find an ATM and change some

money ready for the border. As we stepped aboard the driver clocked us closed

the doors, banging my shoulder and nearly trapping me outside. It stings. The

only way to cope is not to take it personally, but you just can't relax. You’re on edge the whole time, waiting for something to happen.

The next day we set off towards the border. As we left the hotel we discovered that the

white-man fee that had been knocked off by the manager had been replaced by a

mystery tax that pushed the price back up to foreigner rates. We were exhausted

and didn't even bother to argue.

The ride west was horrible. We were tense, got lost,

argued, and flinched every time a car came past. We ducked off the road to calm

ourselves down, and sat there in a café staring at the walls as a little boy

levelled a plastic assault rifle our backs, and fired again and again to the

crackle of motorised gunfire.

A fitting end

Our day needed to go absolutely perfectly if we were to

have any chance of getting to Laos that afternoon, and that didn't

happen. We did manage to get to a town within shooting distance though, and our

motel didn't try any funny business. Rather fittingly though the restaurant

tried some clumsy tactics. We checked the price of everything we ordered as we

ordered it, and when the bill came it was almost double what we’d been told.

Their explanation, once we had reminded them that we knew the price of each of

the dishes, was that the few plies of toilet tissue used to wipe our mouths

were as expensive as a chicken dish. We enjoyed the certainty of catching them

out, told them to stick it up their arse, paid what was due, and left.

I can't tell you the relief we felt about getting out of

there. It was like Christmas Eve and our hearts were pounding. But we were

troubled. We seemed to have fallen out with a whole country.

Neither of us had thought it was really possible – a few bad experiences yes,

but not coming out feeling like half the country hates you.

We tried to find answers from internet forums, and

discovered that we were not alone. Dozens of people reported similar

experiences of constant

unfriendly encounters spilling over into aggression or violence. Theories

abounded as to the cause. Some thought it was racism left over from wartime

propaganda, while others held communism responsible for turning people into

spiteful little trolls. Amongst all of these voices were many people who did

not share our views. Many who had cycled through the country and been met with

nothing but friendliness. A good number who even felt that Vietnam was their

favourite country. We can't argue with that, but we can say, rather objectively

really, that Vietnam treated us far worse than any other country. Bad

experiences were so rare for the rest of the trip that they barely even

registered – one aggressive boatman in Thailand, being charged a bit extra for

water in Indonesia… but these were separated by months of flat out

friendliness. In Vietnam we were dealing with spite and hostility every day, no

wonder only 5% of visitors choose to return.

|

| Our last night in Vietnam was vastly improved when we stumbled across these beautifully stuffed creatures. |

Probably the clearest lesson to emerge out of all this was

how easy it is to become an arsehole yourself. For

instance, we tried to get away from our hotel in Hong Linh without paying for a

couple of drinks. True, they had treated us like dirt and repeatedly lied about

the price of the room, but is that cause to try and rob them? Maybe. I really

don't know. But stealing things is a nasty way of behaving, that's pretty well

accepted I think, and we had no qualms about trying it.

In our junction town hotel near the Vinh Moc tunnels, after

all the hassle with the room price doubling and then the lock being bust, when

it came to check out they fudged up the price and undercharged us – charging us

the extra we'd offered to pay for the first night, but not the second. We

convinced ourselves that this was them compromising with us after all the crap

they'd put us through, but that really didn't ring true. Sure enough, as we

were leaving the black-haired woman came screeching after us, and we found

ourselves caught in the act of trying to do a runner without paying the full

agreed price.

It's easy to become one of them, it really is. One

Vietnamese guy posted in one of the discussions online, saying that foreigners

shouldn't take it personally because everybody, even the locals, get treated

badly. Given our experiences it's easy to see how such behaviour perpetuates

itself once it gets established. Snowballing hatred set in motion by the

country’s divide during the war? Communism? Capitalism? I can’t say, but

something is wrong. We left with the sense that something insidious had

pervaded this country, and made cheating, lying, and abuse a part of everyday life. I realise how bad that sounds, but the problems were so

widespread it’s the only way I can hope to explain it, and convey the intensely bitter taste this country left in our mouths.

It would seem proper to end on a positive note, and praise

the people who showed real kindness towards us since they were doing so under

difficult circumstances. Dwell on the fact that this shows how our own

behaviour has a real impact on the people around us. So be nice, it matters.

That would be the best way to tie things up I think, on a

positive note. But to do that would be dishonest. We were glad to be leaving

Vietnam. With the exception of our week's break in Hoi An we had had bad

experiences right the way through, from the very beginning right up to the end.

It had been deeply unpleasant, and shaken the two of us

up so much it took us weeks to completely get over it. Our concern that

evening as we sat up in our beds wasn't how we could spin this story into

something uplifting, it was: we're not out of the woods yet, we still have to

get across the border.

These concerns weren't enough to suppress the relief we

felt about being so close to getting the hell out of there though. We got under the

covers, knocked the lights off, and fell into a deep sleep. Please Laos, be

gentle with us.

No comments:

Post a Comment